BY Chandrea Miller

Most Americans have seen the commercials of people doing everyday activities as a narrator’s voice tells viewers to “ask your doctor” followed by a long list of the possible side effects.

While pharmaceutical ads feature the latest designer drugs, surprisingly some are for insulin. This is not a new medicine. It’s old. Really old.

Insulin was discovered in 1921 at the University of Toronto by researchers who sold the patent for just $3. They wanted to ensure that anyone who needed the life-saving hormone could afford it.

That did not happen, not by a longshot.

In the United States, insulin costs are five to ten times higher than other developed countries.

But why?

Determined to find out, Neeraj Sood ,PhD, professor and vice dean for research at the USC Price School of Public Policy and senior fellow at the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics, and colleagues conducted a study published in the JAMA Health Forum.

“Consumers are suffering as a result, which means their out-of-pocket prices are going up and they are sometimes rationing their insulin,” Sood said. “We wanted to understand why this is happening?”

The USC cross-sectional study of the U.S. insulin market was conducted in 2020 using 2014-2018 data from multiple sources. The study analyzed the flow of funds throughout the insulin distribution system which includes manufacturers, drug wholesalers, pharmacies, health plans and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). The research team’s objective was to estimate the share of net expenditures on insulin throughout the entire supply chain.

“One way to think about this is when we pay for insulin as consumers–either as premiums or as out-of-pocket costs–that money goes into the supply chain,” he said. “We wanted to understand where does that money go? And how has that changed over time?”

However, following the money would prove challenging.

“Every part of the supply chain is shrouded in these confidential agreements,” Sood said. “We did some detective work and cobbled together data from a variety of different sources.”

These sources included list and estimated net prices from SSR Health for 32 insulin products. SSR Health is a prescription brand pricing data tool that gives clients the ability to assess net pricing at the industry, manufacturer and individual product levels.

“The way they do that is by looking at the financial statements of pharmaceutical firms or looking at investor calls where these pharmaceutical firms are talking with Wall Street analysts, where they disclose how much money they’re making off these drugs,” said Professor Sood.

For decades, it’s been no secret that just three drug companies make up 90% of the global insulin market and that these companies have consistently raised list prices as detailed in the 2021 U.S. House Committee on Oversight and Reform Report.

While Sood’s research also found that insulin prices rose–roughly 40% from 2014-2018–his study surprisingly revealed that drug manufacturers may not be the usual suspects responsible for the price hikes.

“What manufacturers got, after all the discounts they paid, actually went down by 30%. So, you would think that the manufacturers are making less, the overall cost of the system should be going down,” Sood said. “Now, if you combine these two pieces of information: manufacturers are making less, but the net cost of the system is the same–that means the middlemen or intermediaries must be making more.”

A lot more.

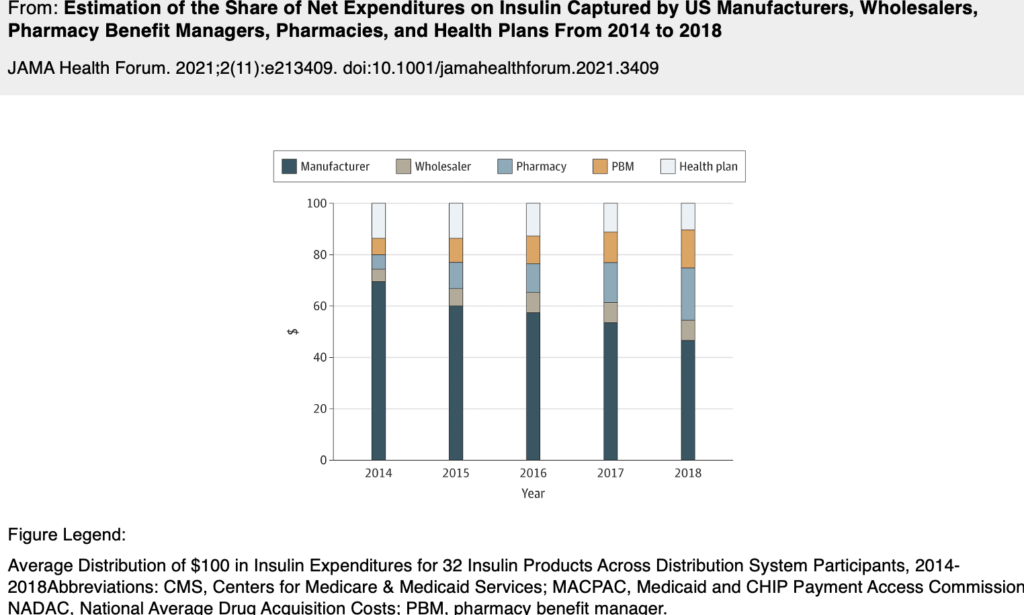

According to the USC study, in 2014, 70% percent of insulin revenue was going to the manufacturers and 30% of the insulin revenue went to the middlemen, but by 2018, only 47% was going to the manufacturers. The middlemen—mostly PBM’s and pharmacies–were pocketing the rest, a whopping 53% share of revenue from insulin sales.

The PBMs garner less attention, but they play an influential role in the insulin supply chain. In fact, PBMs decide which drugs get placed on a “formulary.” This is a list of drugs that insurance will cover. Therefore, pharmaceutical companies often reward PBMs with big rebates.

Rebates that, in part, are supposed to be passed on in savings to the patients like 26-year-old Alec Smith. Alec died in 2017 less than a month after he aged out of his mother’s health insurance plan and couldn’t afford to pay for his insulin.

Alec is not alone.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an estimated 130 million adults are living with diabetes or prediabetes in the United States. Many of those people rely on insulin to stay alive but find themselves priced out.

Twenty states and the District of Columbia have capped copayments on insulin and the recent Inflation Reduction Act caps the cost of insulin at $35 per month for seniors who have Medicare.

Professor Sood says it’s a step in the right direction, but it doesn’t go far enough.

“It shields consumers partially because they don’t have to pay out-of-pocket, but it’s not addressing the fundamental reason why insulin costs are going up,” Sood said. “We’ve got to look at other entrants and look at other people in the supply chain and look at what we can do to change their business practices.”

Policies to control insulin costs should consider all entities throughout the insulin distribution system, conclude Sood and colleagues in the 2021 study. Professor Sood proposes enacting policies that push insulin supply chain pricing transparency and increase government drug pricing negotiations.

Or as he puts it–“Pursue the truth.”

In addition to Sood, Karen Van Nuys, Rocio Ribero and Martha Ryan coauthored the 2021 JAMA Health Forum study on insulin expenditures.